The NMAI has assembled a selection of images that encapsulate the historical importance and glamor of the Gilded Age.

The Gilded Age in American history refers to the period spanning roughly from the 1870s to the early 1920s, an era characterized by significant economic growth, industrialization, and the accumulation of immense wealth by a small portion of the population. As the economy grew at an unprecedented rate, only a small percentage of the country benefited from the financial influx. In fact, only two percent of American households reportedly owned more than a third of the country’s wealth, and the top ten percent owned three-quarters of it. The working class suffered tremendously, but the rich Americans flourished, and lived lavishly as a result.

The term "Gilded Age" was coined by Mark Twain who was making fun of the upper class and their overly opulent styles, even if it was merely for the surface appearance of wealth and extravagance. Frequently, objects were simply painted or coated to appear as if they were made of gold, when in fact it was merely for show. It was a period of both tremendous economic growth and significant social challenges, setting the stage for future reforms and changes in American society and politics.

Newport, Rhode Island, served as a seasonal epicenter of the wealthiest of Americans during The Gilded Age. A short trip from the economic center of New York City, the country’s elite transformed the “City by the Sea” into its Gilded Age playground, and it remains as a monument to this period in American History to this day. This exhibition offers a visual journey through the themes and narratives of the Gilded Age, within the setting of Newport itself. The illustrations will provide historical context and immerse viewers in the opulence, ambition, and social dynamics of the time. The exhibition celebrates the significance of American Illustration in capturing this transformative period in history.

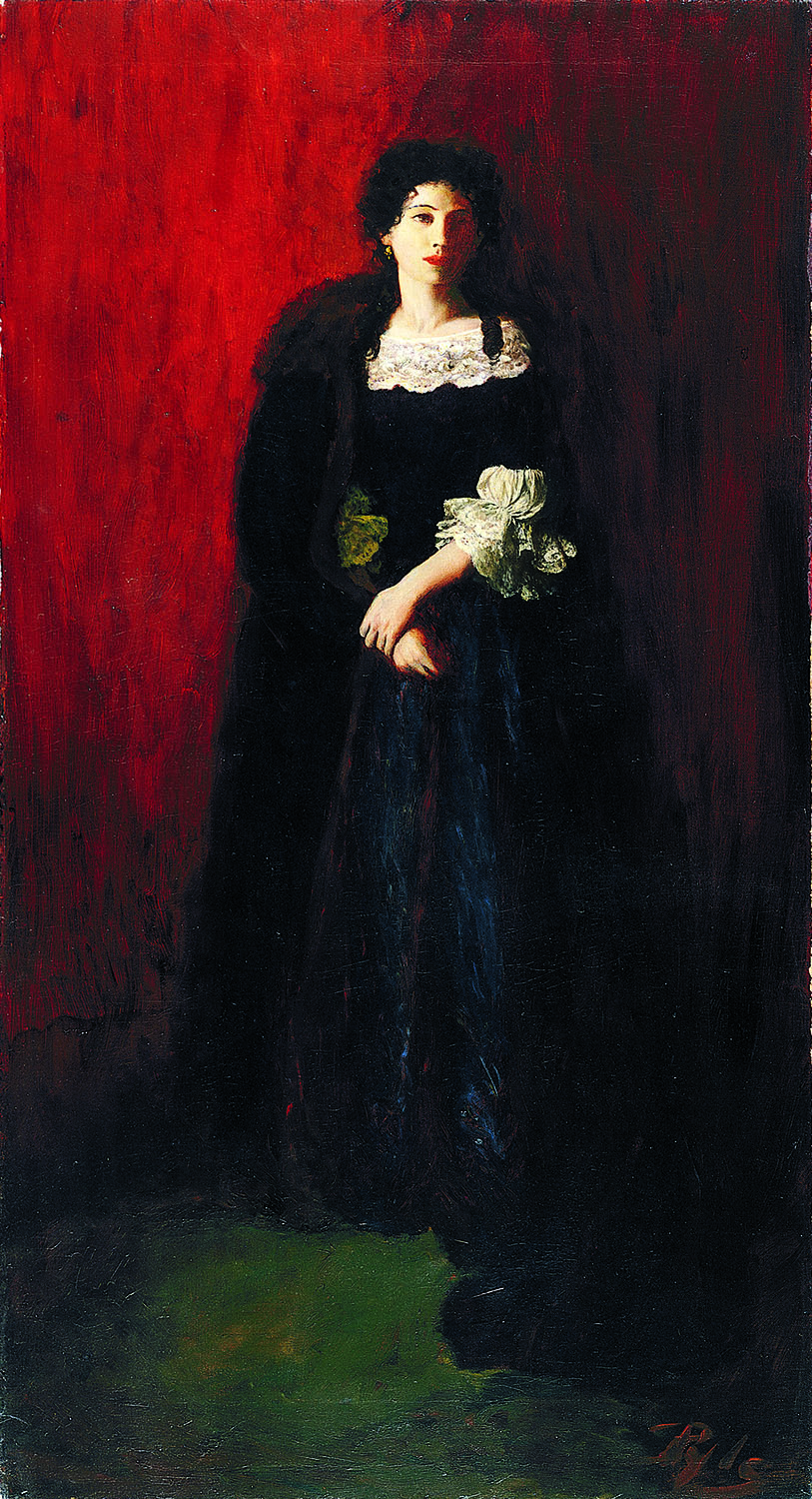

J.C. Leyendecker (1874-1951)

Victorian Lady at the Opera

1905, oil on canvas

26" x 18", signed lower left

Success Magazine, February 1905 cover

Alva Smith Vanderbilt, and later Alva Belmont, was a queen of Gilded Age royalty, playing a significant role in the high society of New York City and Newport, RI. Alva married William Kissam Vanderbilt, grandson of Commodore Cornelius Vanderbilt, in 1875. Alva worked to bring the Vanderbilt family to the pinnacle of society, opening her city block mansion on Fifth Avenue with a masquerade ball in 1883 that was rumored to cost more than a quarter of a million dollars, more than $5 million in today’s dollars. Alva and William build Newport’s Marble House as their “summer cottage”. The project was completed in 1892 and reportedly cost $1.1 million, or $37.2 million in today’s dollars.

In 1895, Alva and William divorced, and she remarried O.H.P. Belmont. Alva continued to fight for her dominant role in high society, moving to Newport’s Belcourt and a new mansion in New York City. Alva became involved in modern causes that interested her, particularly the founding of the National Women’s Party to promote women’s suffrage and the founding of the Metropolitan Opera.

Leyendecker’s Success Magazine cover of 1905 bears a striking resemblance to Alva Vanderbilt, appropriately set in her beloved opera box. The elaborately detailed dress, extravagant jewels and headpiece all appropriately place the famed Alva atop society at her Metropolitan Opera.

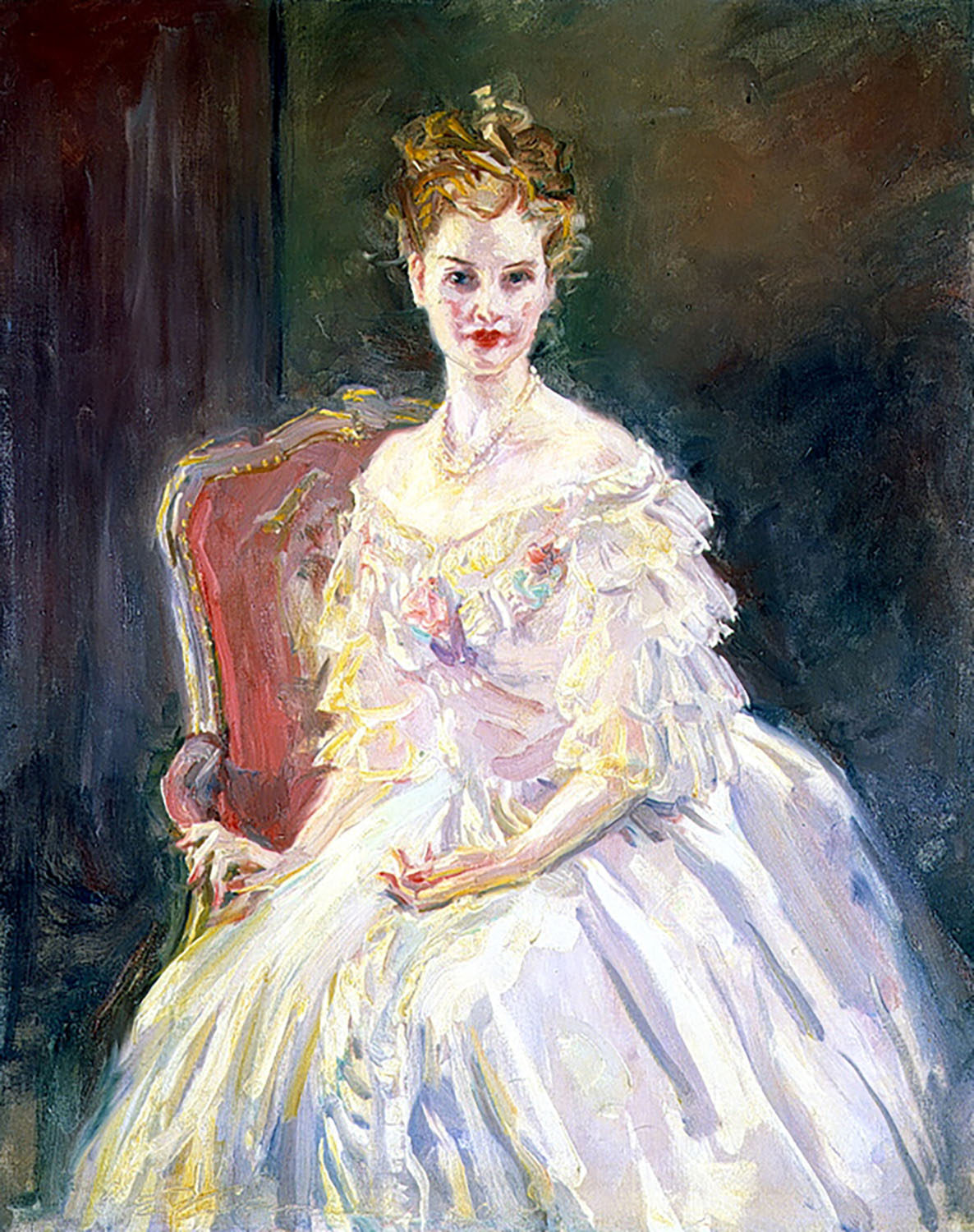

Harrison Fisher (1875-1934)

Lady in Red Chair

1903, watercolor on board

24" x 14", signed and dated lower right

Saturday Evening Post, April 25, 1903 cover

The wife of William Backhouse Astor Jr., Caroline Webster Schermerhorn Astor was best known as “the Mrs. Astor,” preeminent queen of New York City and Newport society. Residing on Fifth Avenue (where the present-day Temple Emanu-El sits) and at Beechwood estate in Newport, Mrs. Astor was known to be the gatekeeper to “The 400”, the elusive highest echelon of American Society. 400 also happened to be the number of guests that could fit in Mrs. Astor’s ballroom, coincidence or not. These events, and others of the “Aristocracy” of New York were closely guarded, only accessible by personal invitation. They were dependent on their exclusivity and dominated by strong willed women with unlimited funds. Mrs. Astor represented the Old Money of America, with families of well-established wealth and prominence. They frequently found conflict with the “New Money” families, most notably the Vanderbilts, and fought to maintain a higher social status, albeit only for a short time more.

Harrison Fisher’s Lady in Red Chair closely resembles Mrs. Astor as she would preside over her lavish parties to the fever of high society.

Alexandre Jacques Chantron (1842-1918)

Still Life with Flowers

1881, oil on canvas

35" x 45 3/4", signed and dated lower left

This monumental still life hung at Newport's Beechwood, the summer cottage home of William Backhouse Astor Jr., and his wife Caroline Webster Schermerhorn, who was known as "the Mrs. Astor."

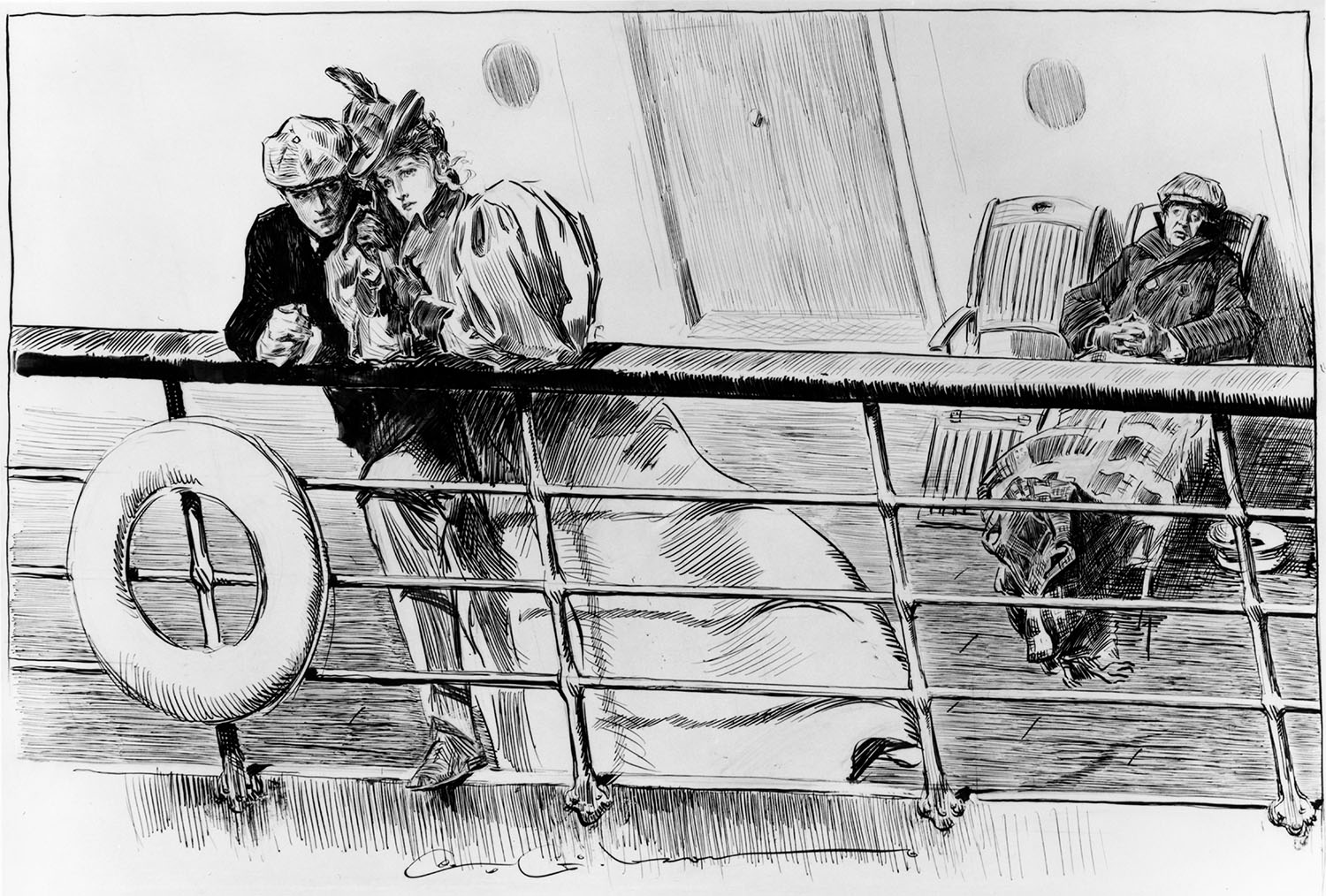

Charles Dana Gibson (1867-1944)

Ill Blows the Wind That Profits Nobody

1897, ink on paper

18 1/4" x 27", signed lower middle

Life's Picture Gallery, by Charles Dana Gibson, Life Publishing Co., 1899

Mrs. Eleanor Elkins Widener was an American heiress, socialite, philanthropist, and adventuress, who built and resided in the Miramar mansion in Newport, Rhode Island, as well as at Lynnewood Hall in Pennsylvania. She was renowned for her beauty, and in 1883 married the son of her father's business partner, George Dunton Widener. In 1912, Eleanor traveled on the RMS Titanic's maiden voyage with her husband and their son, Harry. Unfortunately, Eleanor and her maid were the only members of the family to survive the horrific sinking of the ship. At the time, their Newport mansion, Miramar, was in the middle of construction. Eleanor vowed to completed the home in honor of her late husband and son, and she hosted a large celebratory reception at the completed home on August 20, 1915.

Harrison Fisher (1875-1934)

American Beauties - Frontispiece

1909, watercolor on board

27 3/4" x 20", signed and dated center left

American Beauties, by Harrison Fisher, Bobbs-Merrill Company, NY, November 1909, frontispiece

Harrison Fisher's portrait for his book American Beauties strike a remarkable resemblance to Mrs. Eleanor Elkins Widener. She remarried in October 1915 to a Harvard professor, surgeon and adventurer Alexander Hamilton Rice Jr. Eleanor accompanied her new husband on his South American expeditions, and in 1920 "went further up the Amazon than any white woman had penetrated."

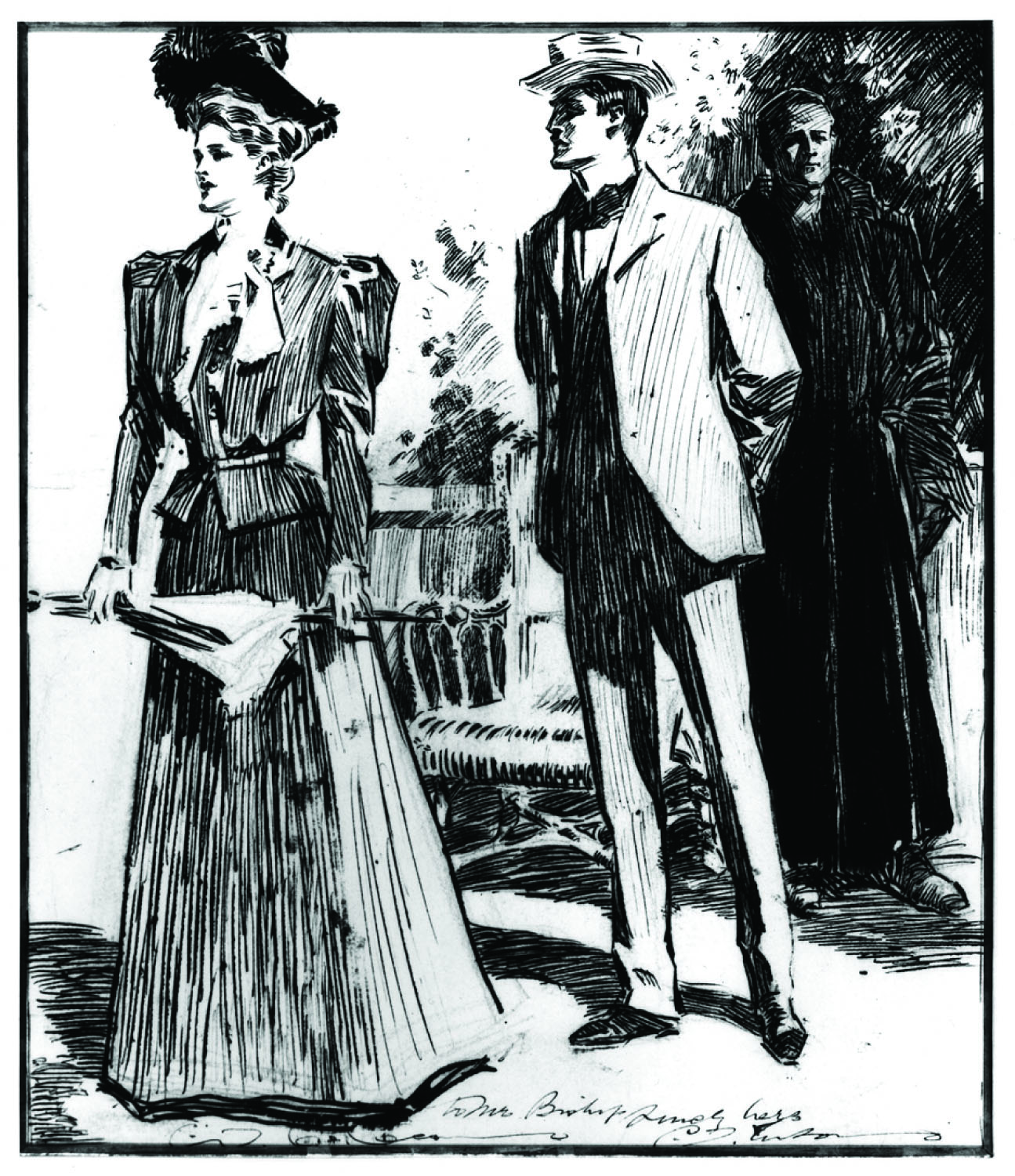

Walter Granville Smith (1870-1938)

Vanderbilt - Neilson Wedding Portrait

1903, gouache, ink and charcoal on board

22 1/2" x 15", signed lower left

Harper's Weekly, April 13, 1903 cover

Advertising poster for the April 13, 1903 issue of Harper's Weekly

In 1903, Reginald Claypoole Vanderbilt, the youngest son of Cornelius Vanderbilt II and Alice Claypoole Gwynne, married Cathleen Neilson, the daughter of Isabelle Gebhard Neilson, at Parker Cottage in Newport, Rhode Island. Reginald's father, Cornelius II built and resided in Newport's The Breakers, the largest of the City's summer residences.

Albert Herter (1871-1950)

Portrait of Nabeia Gilbert of Newport, RI

c. 1900, oil on canvas

60" x 40", signed upper right

Herter's father was a principal in the Herter Brothers furniture-making / interior decoration concern that served the rich in the late 19th century. This granted Albert access to a wealthy clientele in need of a talented portrait artist. Working out of New York and California for most of his career, Herter provided portraiture services to much of high society. Portrait of Nabeia Gilbert is a beautiful example of his portraits, displaying the young aristocrat in a modern dress with a low neckline, exposed arms, and lack of a corset. The intimate lighting of the composition give this portrait a more personal, intimate feeling intended for personal viewing in the home.

Philip Boileau (1864-1917)

Lillian Russell

1905, pastel

27" x 19", signed lower left

Lillian Russel was one of the most famous actresses and singers of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, renowned for her beauty and style as well as her voice and acting. For many years, Russell was the foremost singer of operettas in America. Her voice, stage presence and beauty were the subject of a great deal of fanfare in the news media, and she was extremely popular with audiences. Actress Marie Dressler observed "I can still recall the rush of pure awe that marked her entrance on the stage. And then the thunderous applause that swept from orchestra to gallery, to the very roof.” When Alexander Graham Bell introduced long-distance telephone service on May 8, 1890, Russell's voice was the first carried over the line. From New York City, Russell sang the saber song from La Grande-Duchesse de Gérolstein to audiences in Boston and Washington, D.C.

Z.P. Nikolaki (1875-1934)

After the Ball

1914, oil on canvas

39 1/2" x 39", signed lower right

Saturday Evening Post, February 27, 1915 cover

A prominent American socialite and elite member of American society, Theresa “Tessie” Fair Oelrichs was a resident of New York City’s Fifth Avenue and Newport’s Rosecliff. After Mrs. Astor “retired” as the figurehead of New York society, Tessie was one of the women to take on her social arbiter role. She was known for her strict adherence to the rules of polite society, treating "Society as business.”

Albeit a more informal portrait, Nikolaki’s After the Ball depicts the aftermath of a lavish evening ball. Once the guests have left and the staff is working to ready the cottage again for the morning, the hostess must review the evening’s affairs to prepare for the next day's leisure activities.

Charles Dana Gibson (1867-1944)

Portrait of Artist's Wife, Irene Langhorne

oil on canvas

36" x 27 1/4", signed lower right

Charles Dana Gibson (1867-1944)

Portrait of Artist's Daughter, Irene Langhorne Neé Gibson Post (Mrs. John J. Emery

1938, oil on canvas

45 1/2" x 36 1/2", signed and dated lower left

On November 7, 1895, famed illustrator Charles Dana Gibson married Irene Langhorne, a daughter of railroad industrialist Chiswell Langhorne. Irene was born in Danville, Virginia, one of five sisters all noted for their beauty. Irene became the primary model for Gibson and the inspiration for his infamous “Gibson Girl.” Irene and Charles had two children, a daughter named Irene Langhorne and a son named Langhorne.

Irene Langhorne Gibson married George Browne Post III, a grandson of famed architect George B. Post in 1916. The couple divorced in 1926, and Irene married real estate developer John J. Emery that same year. Emery played a significant role in the development of Cincinnati, Ohio.

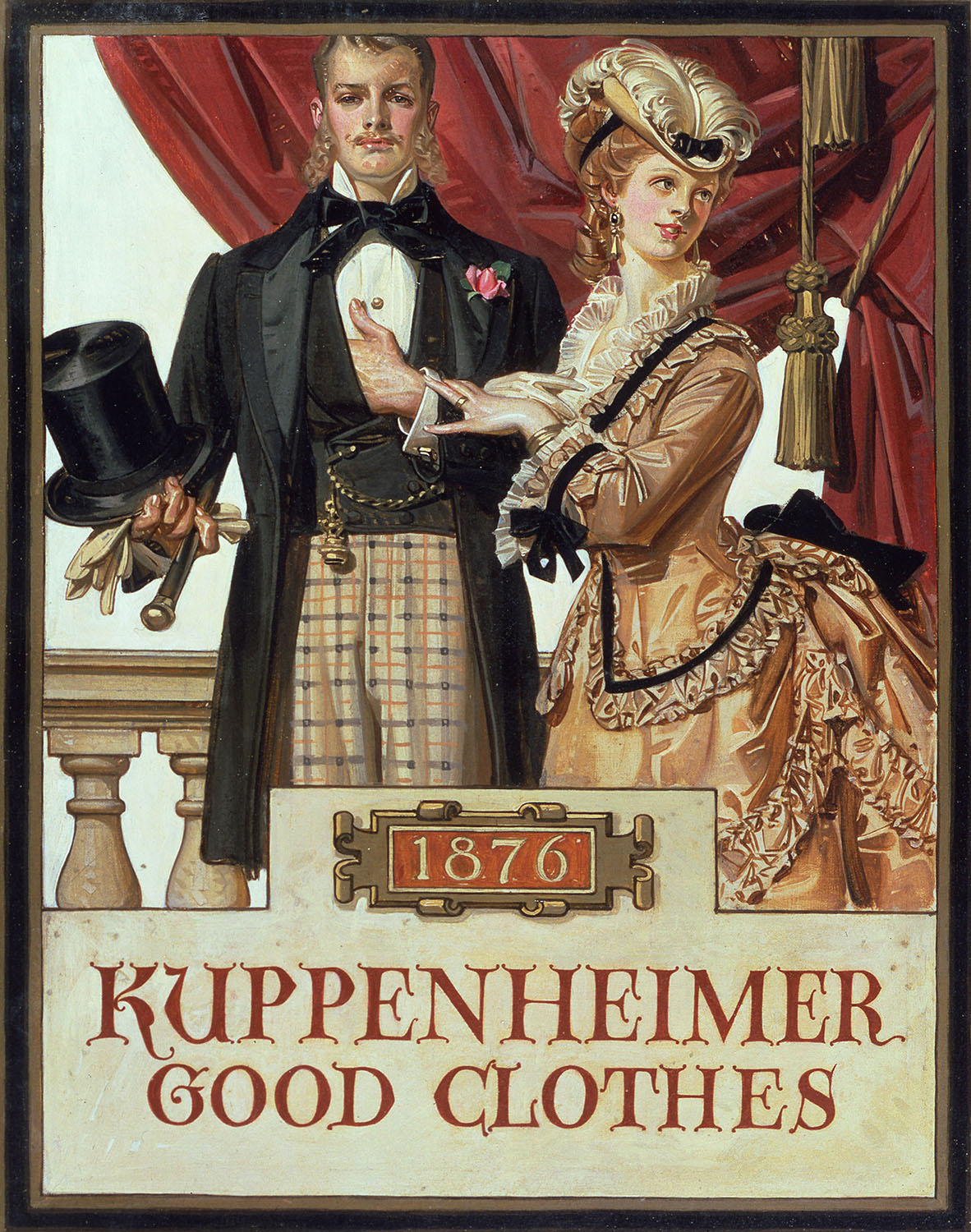

Fashion

True to its name, The Gilded Age was a time of extravagant fashions and new styles, particularly for the women of the upper class who had excessive funds and a social status to maintain. Both men and women were expected to change clothing as many times per day as their social status and wealth would allow. It was common for the wealthy to have different clothing or sporting attire for the morning, afternoon, and evening.

The 1870s were defined by the bustle in women’s gowns and cinched corseted waists. The dresses were in bright, vibrant colors to show off the latest development of these types of dyes. The 1880s saw an elaboration of the bustle trend, with more complicated embellishments and layers incorporated into women’s dresses. An 1888 issue of Harper’s Bazar described a dress with “…metallic embroideries of silk cords, and beads-gold, silver, steel, jet and crystal…so encrusted with metallic embroidery as to conceal the fabric on which it is wrought.” In the 1890s, women’s fashions simplified as women’s roles were becoming more diverse and active as the turn of the century approached. While elaborate gowns were still worn for evening affairs, the daytime activities of women required looser, lighter fabrics with less restrictions than the weighted bustles restrictive corsets allowed.

These illustrations explore this world of high society, where opulence and extravagance knew no bounds, depicting the grandeur of New York's elite, from elegant ballroom gatherings to glamorous portraits.

J.C. Leyendecker (1874-1951)

1876 - Kuppenheimer Good Clothes

1926, oil on canvas

26" x 20"

House of Kuppenheimer advertisement, printed in Saturday Evening Post, September 18, 1926

JC Leyendecker’s painting of a couple at the theater in 1876 beautifully illustrates the elaborate dress of the time. The woman’s bustle is very large with many layers of fabric and lace, coming together at her tightly cinched waist. Her elaborate hat with large feathers and ribbons completes her detailed appearance. Equally dapper is her date in a perfectly tailored tuxedo, with his gleaming top hat and glove in hand.

Eugenie Wireman (1874-1961)

Girl in Green Dress

1907, oil on board

21 3/4" x 21 1/4", signed center left

St. Nicholas Magazine, April 1907 cover

Anna Whelan Betts’ The Easter Bonnet and Eugenie Wireman’s Girl in Green Dress display the fashionable daytime attire of the elite. The complicated layering of fabrics and elaborate bonnets display the finest materials available at the time. The bustle of previous years is no longer in style, but the cinched waist and detailed craftsmanship of the skirt display their elevated position in society.

Anna Whelan Betts (1873-1959)

The Easter Bonnet

1904, oil on canvas

21 1/4" x 16 1/2", signed lower right

Century Magazine, April 1904

Harrison Fisher (1875-1934)

Final Instructions

1902, watercolor, gouache, pencil on paper

31" x 22", signed and dated lower right

Harrison Fisher and Albert Wenzell depict the fashionable evening wear at the turn-of-the-century for the upper-class elite. The women are dressed in formal gowns made of elaborate layering of fabrics with perfectly cinched waists and plunging necklines that would not have been worn in the decades before. These women are clearly of the upper-class because such impractical, single-use attire could not be afforded by someone of lesser standings.

Philip Boileau (1864-1917)

Red Poppies

1910, watercolor, gouache and pastel on paper

27 1/4" x 17 1/2", signed lower right

Osborne Co. Calendar illustration, 1910

Philip Boileau captures a woman in the more relaxed fashions after the turn-of-the-century. With lighter lace fabrics and an open neckline, this model embodies the relaxed elegance of a woman spending time outdoors surrounded by the flowers of her garden or a public park.

Leisure

With the growth of an elite upper class came the development of widespread leisure activities, which provided ample opportunity to put their wealth on display.

Harrison Fisher (1875-1934)

At the Opera

1901, watercolor on board

27 1/4" x 19 1/2", signed and dated lower left

In 1883, The Metropolitan Opera House opened in New York City and instantly became a place to be seen in attendance. Harrison Fisher’s At the Opera captures the fashions of the private boxes at the Opera, a symbol of prestige and status. These private boxes offered an exclusive and privileged vantage point for viewing the performances while providing a sense of intimacy and exclusivity. Occupying a box allowed the elite to see and be seen by their peers, reinforcing their social status.

Charles Dana Gibson (1867-1944)

The Hunt Ball

1895, ink on board

22" x 32 1/2", signed lower right

"Pictures of People," Life Magazine, 1895

With the construction of grand estates along New York’s Fifth Avenue and Newport’s Bellevue Avenue, formal balls were a way to put these lavish homes on display. Charles Dana Gibson’s The Hunt Ball captures the elaborate gowns and gentlemen's "pinks" (scarlet coats) of one of these balls for Life Magazine, a means of reporting on the happenings of the upper class.

Walter Granville Smith (1870-1938)

The Promenade: Central Park

1897, watercolor on paper

17 1/4" x 28 1/4", signed and dated lower left

Truth Magazine, 1897, centerfold

At the turn of the century, Central Park was New York City’s public runway for the elite to enjoy a respite from the chaotic city streets. Designed by famed landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted, Central Park opened to the public in 1858 and would continue to develop over the next 15 years to public acclaim. Walter Granville Smith captures the elegance of the Park’s exquisite landscape in The Promenade.

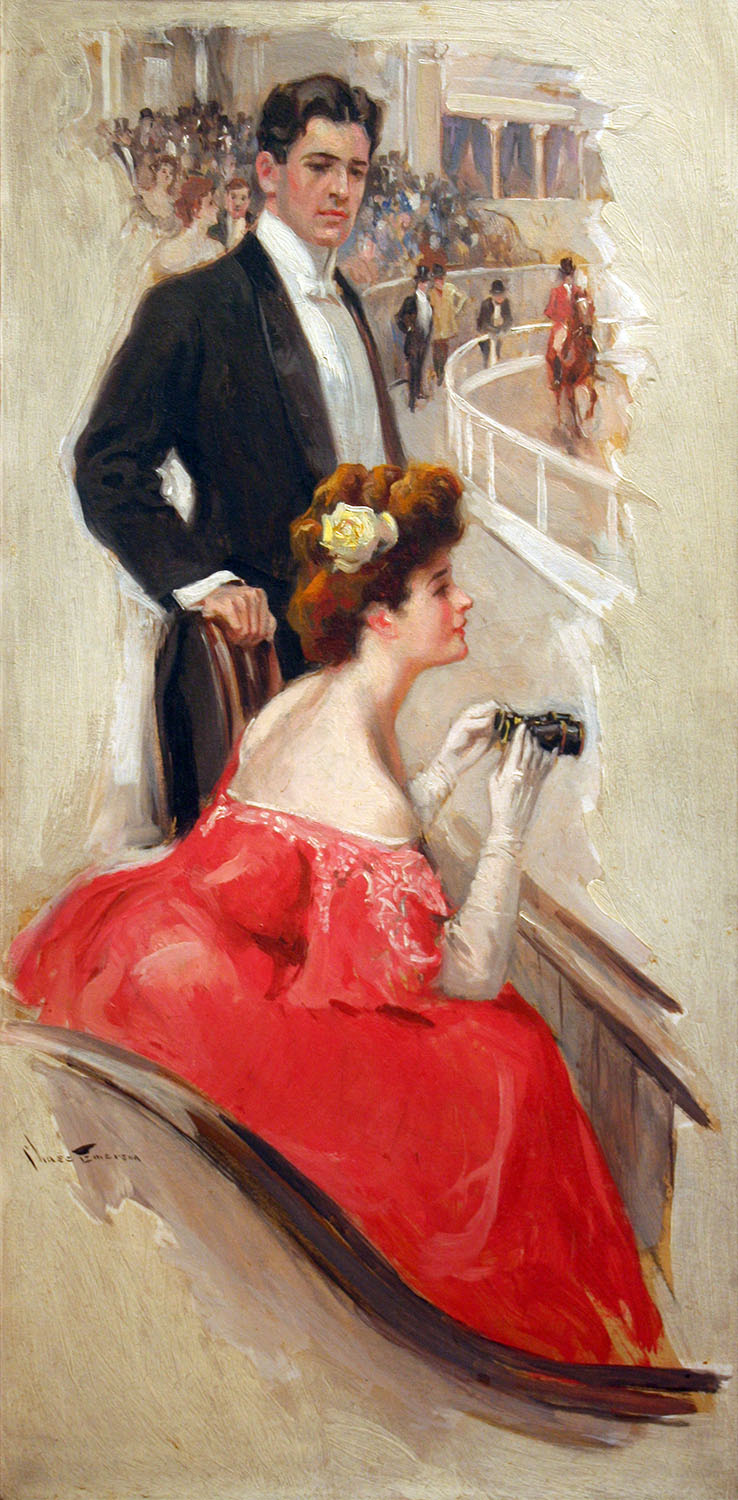

Chase Emerson (1874-1922)

Couple at Dog Show

1905, oil on board

27 1/2" x 13", signed lower left

The first ever dog show was held in May 1877 at Gilmore’s Gardens on New York City’s Madison Avenue. At a time when hunting with sporting dogs was a popular activity among society’s elite, a way to display their finest dogs became a huge hit. Up to 8,000 New Yorkers attended the show on the first day, followed by 10,000 on the second and third days. “Everybody was fashionably dressed and wore an air of good breeding,” wrote The New York Times. In the following years the show was moved to Madison Square Garden to accommodate the growing popularity. In 1907, the first “Best in Show” award was given to a fox terrier named Warren Remedy.

Chase Emerson’s 1905 illustration captures the elegance of these popular dog shows. The gentleman are in their best white collared tuxedos with gleaming top hats, and the women are in their formal day dresses with elaborate hats.

Henry Hutt (1875-1950)

Saturday Afternoon at a Country Club

1900, gouache on board

28" x 19", signed lower right

Illustration appearing in Harper's Weekly, September 9, 1900, pg. 841

Chase Emerson (1874-1922)

Couple at Horse Race

oil on board

27 1/2" x 13 1/2", signed lower left

During the Gilded Age, horse racing transcended mere sport, evolving into a grand social spectacle interwoven with the fabric of high society. Dressed in the era's finest fashions, elites like the Vanderbilts and Whitneys flocked to opulent racetracks, such as the iconic Churchill Downs inaugurated during this period. The emergence of the Triple Crown series and the introduction of the Daily Racing Form became hallmarks of this age. Technological innovations, including the photo finish camera, enhanced the experience, while the boom in thoroughbred breeding signified the sport's prominence. This opulence and fervor are palpably captured in Chase Emerson's Couple at Horse Race, where a well-dressed couple, representing the era's elite, immerse themselves in the thrilling ambiance of a race, with the lady keenly following the contest through her binoculars, encapsulating the era's passion for the sport.

Music

The Gilded Age was a time that America developed its own styles in music apart from the European trends that had prevailed until this time. Music became a means of entertainment for wider audiences with symphonies that traveled across the country on the newly developed train railways, as well as the popularity of musicians playing in open, public spaces. Music was also brought into the home with the ubiquitous parlor piano, which promoted the creation and sale of sheet music.

Harrison Fisher (1877-1939)

Lady and Her Suitor

1909, watercolor and gouache on paper

21 3/4" x 15 5/8", signed and dated lower right

Gathering around the family’s piano became a common pastime in America, and a favorite scene for many illustrators, including Harrison Fisher, Charles Dana Gibson, and Hamilton King. These illustrations capture upper-class women in the home displaying their well-developed talents at the piano. Each woman embodies the elegance and glamour that epitomizes the Gilded Age.

Harrison Fisher (1875-1934)

Woman at Piano - Oh! Promise Me

1910, watercolor on board

25 1/4" x 16 3/4", signed lower left

Saturday Evening Post, January 15, 1910 cover

"Fair American’s," by Harrison Fisher, Charles Scribner’s Sons, September 23, 1911, illustration #24

"American Girls in Miniature," by Harrison Fisher, Charles Scribner’s Sons, August 24, 1912, illustration #12

Written in 1887 by Reginald De Koven with lyrics by Clement Scott, Oh Promise Me was first published as an art song in 1889. In 1890, De Koven used the song in his successful comic opera, Robin Hood, to highlight the star contralto's vocal range. The song became a huge success, selling over a million copies in that year alone.

Oh, promise me that someday you and I

Will take our love together to some sky

Where we can be alone and faith renew,

And find the hollows where those flowers grew,

Those first sweet violets of early spring,

Which come in whispers, thrill us both, and sing

Of love unspeakable that is to be;

Oh, promise me! Oh, promise me!

Oh, promise me that you will take my hand,

The most unworthy in this lonely land,

And let me sit beside you in your eyes,

Seeing the vision of our paradise,

Hearing God's message while the organ rolls

Its mighty music to our very souls,

No love less perfect than a life with thee;

Oh, promise me! Oh, promise me!

Hamilton King (1871-1952)

Lady at the Piano

1900, watercolor on paper

21" x 16 1/2", monogrammed left center

Victorian Greeting Card, 1900

Charles Dana Gibson (1867-1944)

Studies in Expression

pen and ink on board

19 3/4" x 15 1/2", signed lower left

Musical aptitude was frequently passed down through generations, particularly if private tutors could not be afforded. Charles Dana Gibson captures this tradition in his drawing of a young girl practicing her songs at the piano with her mother’s guidance, while her father enjoys the music.

Alice Barber Stephens (1858-1932)

Sweet Harmony

c. 1900, oil on canvas

23" x 17", signed upper right

While music became more widespread during the Gilded Age, something to be shared with the public in outdoor concerts and social gatherings, one of the most popular places to hear music was still in religious settings. Alice Barber Stephens’ Sweet Harmony highlights a young woman performing with a church choir.

Albert Beck Wenzell (1864-1917)

At the Piano

1890, oil on canvas

26" x 20", signed and dated lower right

Harper's Magazine, Christmas issue, 1890

Sport

The Gilded age saw the commodification of sports culture that exists in modern American culture. An industrializing economy and a growing middle class led to American workers having more disposable income and free time than they’d ever had in the past. Attending and rooting for college and professional sports teams became an important part of leisure time for men and women. Individual sports like golf, cycling and horseback riding were also immensely popular.

As women increasingly left the domestic spere in the late 19th century, they were encouraged to get fresh air and exercise. Sporting activities such as riding, hunting, tennis and golf provided just as well as a social activity. These activities required a wardrobe of their own, and sportswear of loose blouses and skirts became essential for performing these activities.

Harrison Fisher (1875-1934)

Following the Race (Woman with Bamboo Riding Crop)

1910, oil on board

22 3/8" x 17 3/8", signed lower center

Saturday Evening Post, November 5, 1910 cover

"American Girls in Miniature," by Harrison Fisher, Charles Scribner's Sons, August 24, 1912, illustration #7

"Fair Americans", by Harrison Fisher, Charles Scribner's Sons, September 23, 2011, illustration #12

Harrison Fisher and JC Leyendecker capture women in high riding fashion for the covers of the Saturday Evening Post and Collier’s magazines. Fisher’s attention to detail in the woman’s bamboo riding crop and leather riding gloves in her right hand complete this illustration without the need to include the horse at all. Meanwhile, Leyendecker beautifully painted the horses in his cover to appeal to the equestrian viewers. The gentleman and his horse seem to bow together as they greet the elegant woman in the background, while she and her horse seem to be assessing the duo before deciding if she should engage.

J.C. Leyendecker (1874-1951)

Couple on Horseback

1904, gouache on board

17" x 17 1/2", signed lower left

Collier's Magazine, May 7, 1904 cover

Charles Dana Gibson (1867-1944)

The Story of the Hunt

1898, pen and ink on paper

18 1/2" x 26 1/2", signed lower right

Sketches and Cartoons, by Charles Dana Gibson, R.H. Russell, New York, 1898

An activity previously reserved for men, hunting became a popular activity for women as well with the increased popularity of riding and outdoors adventures. Charles Dana Gibson and Walter Granville Smith capture the style of such activity in their illustrations of women taking up arms to hunt for foxes and turkeys.

Walter Granville Smith (1870-1938)

Fox Hunt

1898, oil on canvas

27" x 22", signed lower right

Walter Granville Smith (1870-1938)

Woman Fair and Turkeys Wild

1894, watercolor and gouache on board

15" x 25", signed and dated lower right

Truth Magazine, 1894, centerfold

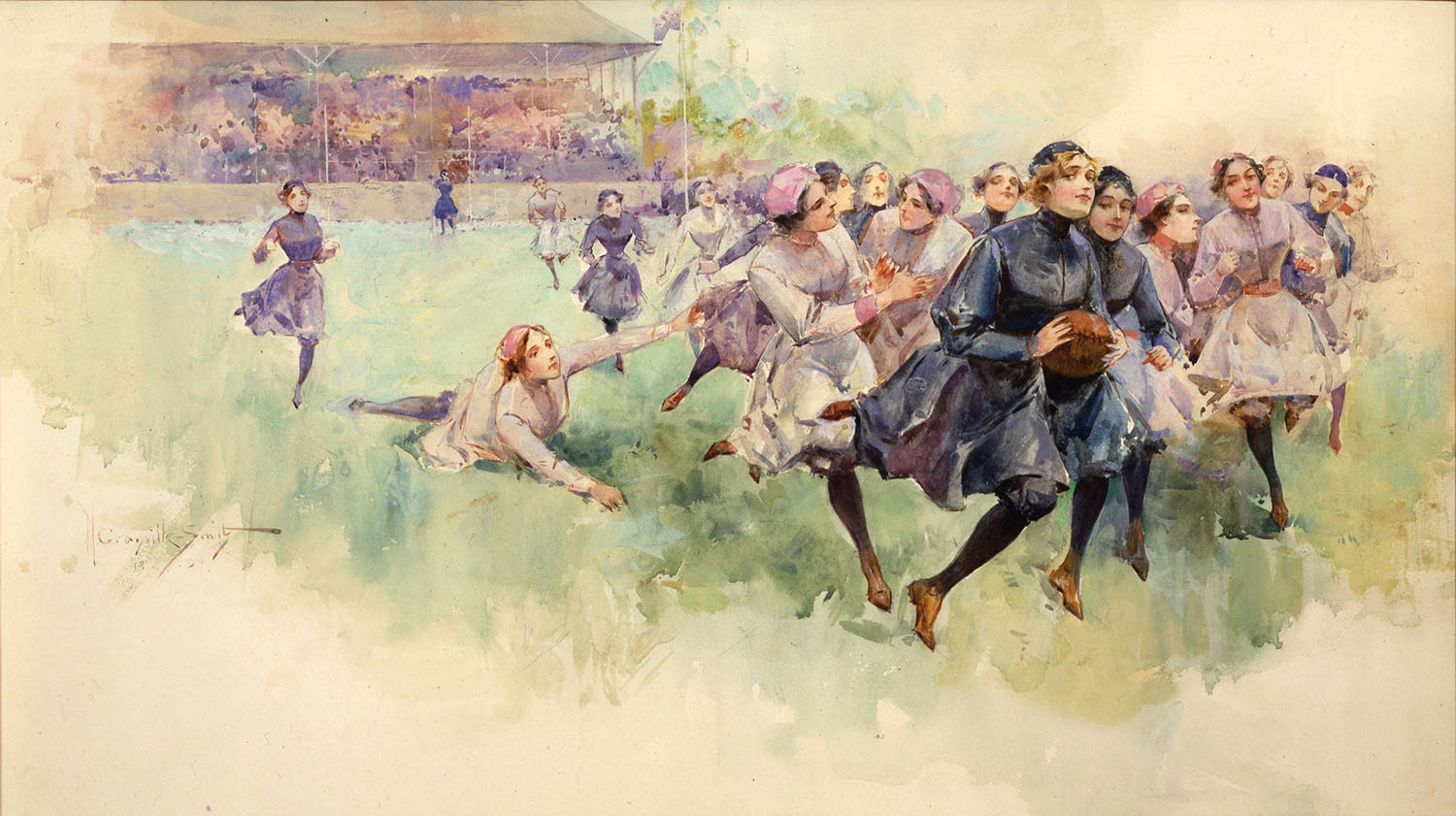

With increased free time for the newly developing middle class, organized sporting events became more popular on local, collegiate, and professional levels. Attendance at these sporting events was as important as participating in the sport itself, with audiences growing in size and passion for the action occurring on the field. Arthur Keller displays the earliest forms of “tailgating” at a University of Pennsylvania vs. Princeton football game, with carriages parked along the edge of the field. Walter Granville Smith illustrates women playing rugby in the modest yet fashionable uniforms of the times.

Arthur I. Keller (1866-1924)

Penn and Princeton Meet at a Football Game

1905, gouache on board

17" x 27", signed lower left

Truth Magazine centerfold

Walter Granville Smith (1870-1938)

Girls Rugby

1894, watercolor on board

15 1/2" x 26 1/2", signed and dated center left

Truth Magazine centerfold, 1894

Transportation

Railroads completely transformed the United States socially, politically, and economically during the Gilded Age. Literally the engine of the new industrialized economy, they facilitated the speedy transportation of raw materials and finished goods from coast to coast. By 1900, the United States boasted almost a quarter of a million miles of railroad track. As consolidation and innovation streamlined costs, it became cheaper and faster to ship raw materials, manufactured goods, foodstuffs, and oil, as well as passengers, via rail than by steamship.

By 1900, mass production of automobiles had begun in the United States and in 1908 the famed Model T became the first mass-affordable automobile, revolutionizing the way Americans traveled. The mass availability of the automobile became an instant success, and by 1927, less than 20 years later, Henry Ford sold his 15 millionth Model T.

The expansion of the rail system and mass production of automobiles changed the way Americans lived their everyday lives. Travel beyond the neighboring town was now feasible for the average American, not just the wealthy. This allowed for people to live farther from their jobs, promoting urban sprawl, and the ability to travel for leisure.

Edward Penfield (1866-1925)

A Day of Leisure

c. 1914, gouache

18" x 37 3/4", signed lower right

Hart Schaffner & Marx clothing advertisement, c. 1914

Even with the rapid development of the automobile, it would be some time before the traditional horse-and-buggy means of transportation became a thing of the past. During the Gilded Age, the traditional carriage shared the road with modern automobiles, causing more than one traffic jam and confusion on the shared roadways. Anna Whelan Betts illustrates the traditional large carriage, driven by a team of horses and coachmen. Edward Penfield’s cover for Collier’s Magazine depicts a simpler, self-driven carriage with a single horse, here driven by a woman saying goodbye to the modernly dressed gentleman.

Anna Whelan Betts (1873-1959)

Gold Coins

1904, oil on canvas

26" x 17 1/4", initialed lower left

Edward Penfield (1866-1925)

Good-Bye Summer

1917, mixed media on board

19 1/2" x 17 1/2", signed lower right

Collier's Magazine, September 14, 1912 cover

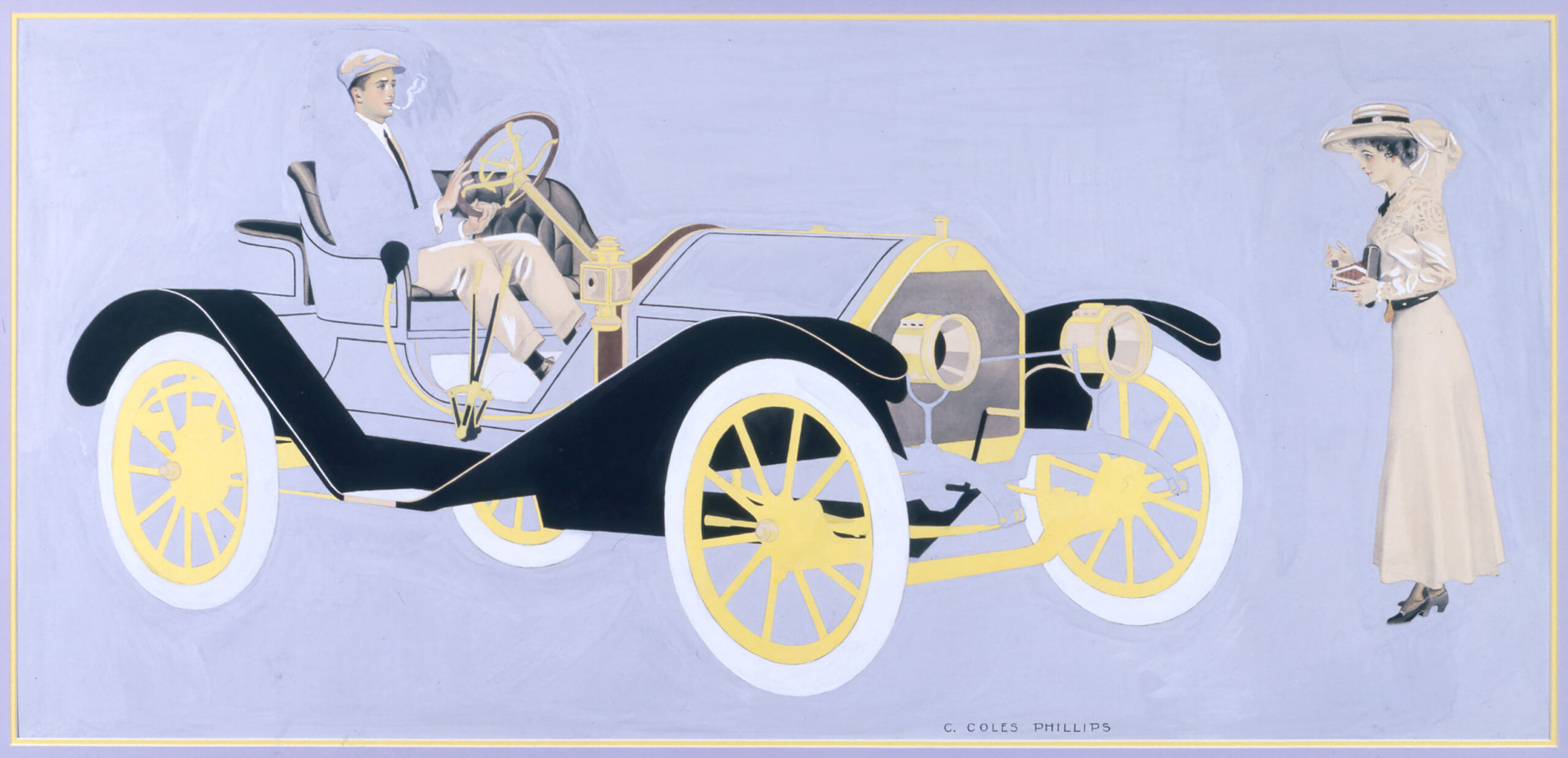

While the Model-T is the most famous of the early cars for its revolutionary use of the assembly line to make automobiles affordable to the masses, there were many producers who followed closely to their example. A new industry of cars and their related materials developed rapidly with the growing demand. Harry Anderson’s illustration from 1967 depicts President William Howard Taft with his wife Helen and son Robert “going for a spin” around the White House in a brand-new 1909 White Steamer. Coles Phillips’ 1910 advertisement for the Hudson Motor Car Company shows the latest model in striking profile, displaying the car’s “grace and style” for the proud new owner’s admirer. McClelland Barclay’s glamorous advertisement is for the luxurious Fisher Body, the interiors they provided for the new automobiles to make them more comfortable for the passengers.

Harry Anderson (1906-1996)

The Chief Executive Goes for a Spin in a 1909 White Steamer

1967, gouache on board

22" x 28", signed lower left

Great Moments in Early American Motoring calendar illustration, November 1967

C. Coles Phillips (1880-1927)

Hudson Motor Car 1910 - Model 20

1910, gouache on board

13 1/2" x 32"

Hudson Motor Car Company advertisement, printed in Literary Digest, August 20, 1910 back cover

McClelland Barclay (1891-1943)

Fisher Body Advertisement

c. 1920, oil on canvas

24" x 29"

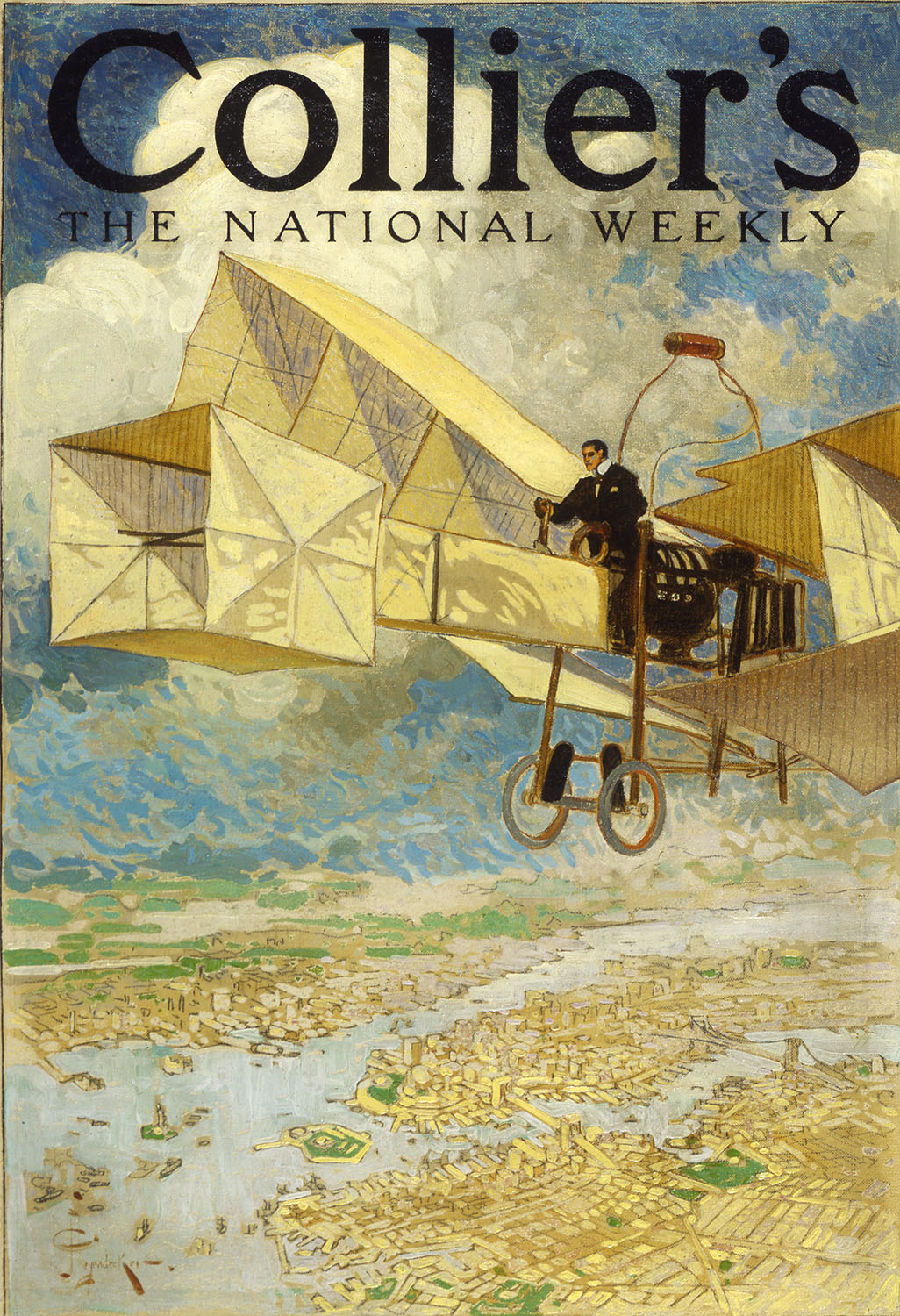

J.C. Leyendecker (1874-1951)

Flight Over Manhattan (When Shall We Fly?)

1907, oil on canvas

25 7/8" x 17 3/4", signed lower left

Collier's, February 23, 1907 cover

On December 17, 1903, Orville Wright and Wilbur Wright, known as The Wright Brothers, flew the first controlled, sustained flight in North Carolina. Over the following years, the public expressed skepticism and unease over man’s ability to fly, but followed the developments with interest. It was not until 1908, when the Wright Brothers began public demonstrations, that the public became more intrigued by the actual capabilities of flight. JC Leyendecker’s cover for the February 23, 1907 issue of Collier’s encapsulates the public’s questioning attitude about the new technology. Leyendecker impressively captures a bird’s-eye-view of Manhattan Island, imagining what the experience of flying over the city would be like. It would not be until the 1920s that commercial flights would begin in the United States, and they would not become popular until the 1950s.

Innovation

During the Gilded Age, the United States experienced an unprecedented surge in technological and industrial innovations. Key developments included the advancements in photography and the printing process, the advent of the telephone, and the introduction of electricity to homes and businesses. These advancements transformed the American landscape, bolstered the economy, and significantly altered daily life for countless individuals.

Elizabeth Shippen Green (1871-1954)

New Kodak

1906, mixed media on board

14 3/4" x 15", signed lower left

Advertisement for Kodak Camera

George Eastman invented and marketed the world’s first personal camera, the Kodak, in 1888. The simple camera came pre-loaded with 100-exposure roll of film for ease of use for the owner. When the camera roll was finished, the entire camera was sent to the factory in Rochester where the film was processed, and the camera was returned to the owner with a new roll installed. By simplifying the camera and handling of the film, Eastman made photography accessible to the public, creating new generations of amateur photographs.

Harrison Fisher (1875-1934)

The Telephone Call

1903, watercolor on board

19" x 15", signed lower right

First patented by Alexander Graham Bell 1876, the telephone revolutionized the way people communicate with each other forevermore. By 1904, over three million phones were in use in the United States. The widespread use of the telephone increased the speed of communication between households and businesses and allowed for long distance and international conversations. Harrison Fisher captured the glamour of speaking on the telephone in his 1903 illustration.

John Clymer (1907-1989)

Samuel Slater Demonstrates the First Successful Textile Machinery

1969, oil on board

30" x 40", signed lower right

American Cyanamid corporate calendar, 1969

Situated on the shore of Greenwich Bay at Cowesett in southern Warwick, RI, Clouds Hill was constructed in 1872-77 by Providence textile manufacturer William Smith Slater (1817-1882). His uncle Samuel Slater (1768-1835), “Father of the American Industrial Revolution”, brought English cotton spinning technology to America and in partnership with younger brother John Slater (1776-1843)--William S. Slater’s father--founded a network of cotton mills and mill towns throughout New England. The new country estate was intended for Mr. Slater’s eldest daughter Elizabeth Ives Slater (1849-1917) on the occasion of her marriage to Alfred Augustus Reed, Jr. (1845-1895) whose family were traders in the Dutch East Indies colony of Batavia (Jakarta) prior to retiring to New England.

Built when McPherson was simultaneously executing the interiors of Chateau-sur-Mer, Newport, under Richard Morris Hunt, the house was never substantially altered and retains all of its original contents together with those of subsequent generations. Emblematic of America’s evolving and trailblazing pursuit of new horizons--technological and social--Clouds Hill today retains its authenticity, not only physically, but also in the preservation of its residents’ personalities and spirit.

Literacy

As the 19th century progressed and the American economy transitioned away from family farming, public education became more important. By 1900, 34 states had compulsory schooling laws requiring attendance of all children until the age of 14. This new emphasis on education was extremely effective at lowering illiteracy among the American public, with the rate falling from 20% in 1870 to only 10% by 1900.

With widespread education, there was a new interest in literature for the public that was previously reserved for the upper class and those who could afford a private education. Publishing houses eager to profit from this new reading audience created the paperback book, an inexpensive way to print new novels for the masses, and serialized novels in magazines for weekly readers to enjoy. These more accessible mediums, combined with cheaper distribution means through the national railway, created a popularity of adventure tales, detective thrillers, and romance stories for the eager public to consume.

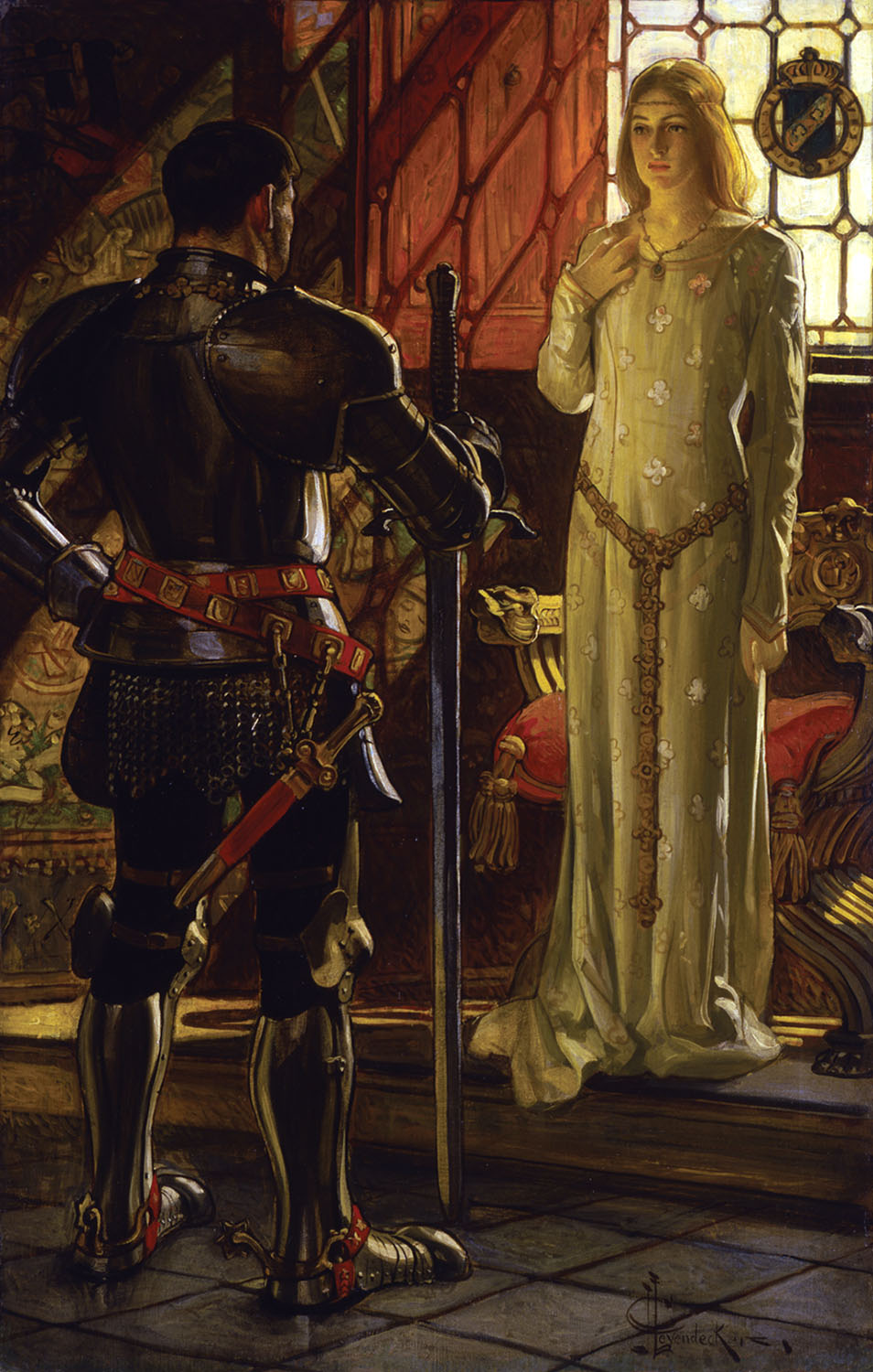

Harrison Fisher (1875-1934)

I Have Won Your Love, Beverly, By The Fairest Means

1904, watercolor and gouache on board

27" x 20", signed lower left

Beverly of Graustark, by George Barr McCutcheon, Dodd, Mead & Company, New York, 1904, pg. 355

The literature and media of the Gilded Age often depicted women in new and more diverse roles. Novels and newspapers featured strong, independent female characters who challenged traditional gender expectations, contributing to discussions about the evolving roles of women.

Charles Dana Gibson (1867-1944)

He Will Get the Best of Us If We Stay

1898, ink and pencil on paper

14" x 12", signed lower left

The King's Jackal, by Richard Harding Davis, Charles Scribner's Sons, New York, 1898, frontispiece

J.C. Leyendecker (1874-1951)

Consolation

1905, oil on canvas

25" x 17", signed lower right

A Victory Unforeseen, by Ralph D. Paine, Scribner's Magazine, July 1905, pg. 15

"He was the little boy who used to flee to that dear sanctuary in every time of trial."

J.C. Leyendecker (1874-1951)

The Crew Were Borne on Tossing

1905, oil on canvas

30 1/2" x 22", signed lower right

"A Victory Unforeseen," by Ralph D. Paine, Scribner's Magazine, July 1905, pg. 16

J.C. Leyendecker (1874-1951)

The Wedding

1909, oil on canvas

15" x 28", signed lower right

The Voice in the Rice, by Gouverneur Morris, Saturday Evening Post, 1909

Howard Pyle (1853-1911)

Diana Sherley

1903, oil on canvas

37" x 20", signed lower right

"The Ultimate Master," by James Branch Cabell, Harper's New Monthly, November 1908, pg. 859

Alice Barber Stephens (1858-1932)

All My Friends Call Me Fanny

1896, watercolor

22" x 14 1/2", signed lower right

"The Assistant Librarian Protemp," by Robert CV Meyers, Ladies' Home Journal, November 1896

J.C. Leyendecker (1874-1951)

Ridolfo and Gismonda

1906, oil on canvas

29" x 18", signed lower right

Ridolfo: The Coming of the Dawn, by Edgarton R. Williams, Jr., A.C. McClurg & Co., 1906

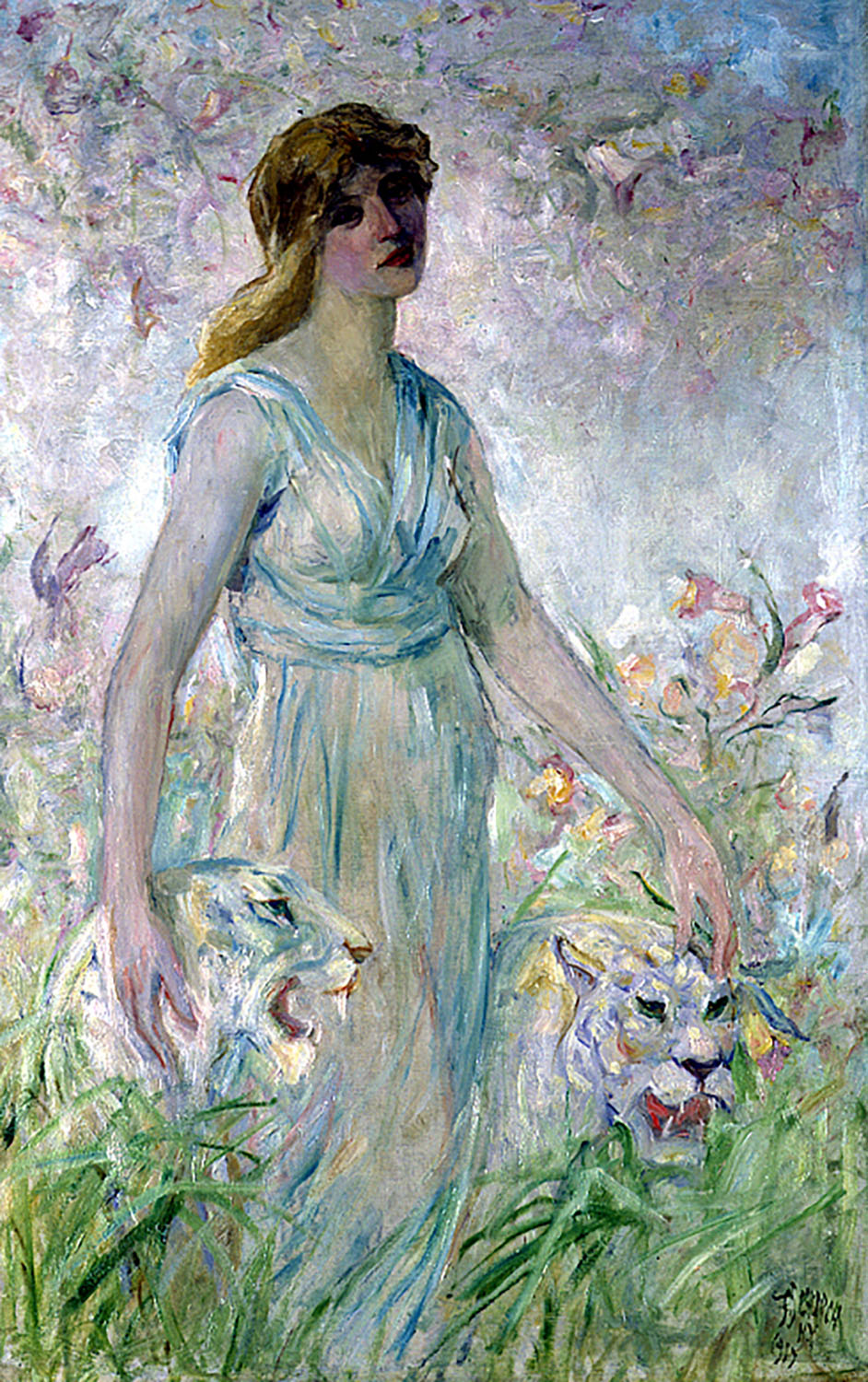

Frederick Stuart Church (1842-1927)

Orchids and White Leopards

1917, oil on canvas

47 1/2" x 30 1/2", signed and dated lower right

Women's Advancement

Witness the evolving roles of women and the societal shifts of the Gilded Age. From discussions about marriage to the pursuit of independence, these illustrations reflect changing norms. This era laid the groundwork for the further advancement of women's rights and the ongoing evolution of gender roles in the 20th century and beyond.

Harrison Fisher (1875-1934)

Graduation

1903, watercolor, tempera, and pencil on paper

18 1/2" x 13 3/4", signed and dated lower right

Ladies' Home Journal, June 1903 cover

Women's roles in education were evolving during this period. The number of women pursuing higher education increased, and the establishment of women's colleges, such as Smith and Wellesley, provided them with opportunities for intellectual growth. This change reflected a growing belief in women's capacity for intellectual achievement and their potential beyond domestic roles.

J.C. Leyendecker (1874-1951)

New Year's Baby - Votes for Women

1911, oil on canvas

26 1/8" x 19 1/8", signed lower left

Saturday Evening Post, December 30, 1911 cover

The Gilded Age saw the emergence and growth of the suffrage movement, which advocated for women's right to vote. Figures like Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton were instrumental in leading this movement. The fight for suffrage reflected changing societal norms as women sought political agency and equal participation in the democratic process.

Howard Pyle (1853-1951)

Women at the Polls in New Jersey in the Good Old Times

1880, gouache on paper

10 3/4" x 17", signed center left

Harper's Weekly, November 13, 1880

Walter Granville Smith (1870-1938)

Planting the Class Tree (Vassar Graduation)

1897, watercolor on board

16 1/4" x 29", signed lower left

The Illustrated American, July 29, 1898

Sarah Stilwell Weber (1878-1939)

Young Girl with Books and Umbrella

1909, oil on canvas

18 1/4" x 21 5/8", initialed lower left

Saturday Evening Post, October 9, 1909 cover

Sarah Stilwell Weber's illustration of a young girl with a determined expression and the prominence of the books hint at the era's growing emphasis on female education. The choice of this image for the cover of the widely read Saturday Evening Post publication reflects the cultural significance of changing attitudes, signaling a broader societal acceptance and the rising value placed on educating young girls.

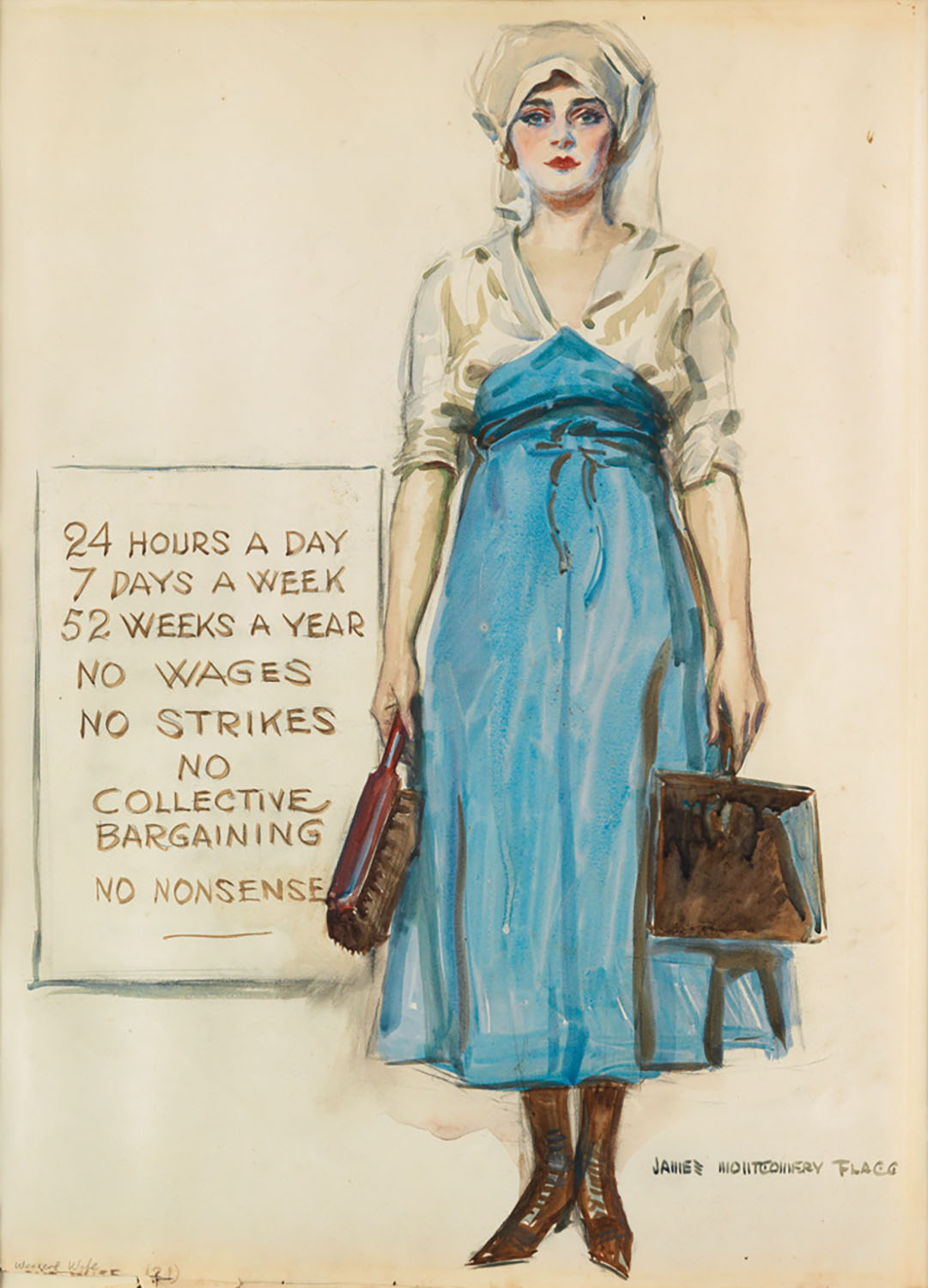

James Montgomery Flagg (1877-1960)

Friend Wife

1920, graphite and watercolor on paper

26 1/2" x 19 1/2", signed lower right

Judge Magazine, May 8, 1920 cover